A young far-right activist puts up a poster near a Helsinki school, condemning Islam and demanding an end to “the stream of terrorists”.

A fanatically religious Muslim man happens to pass by while the activist is putting up the poster.

The man pushes the activist and tears down the poster, resulting in a fistfight and shouting match.

https://vimeo.com/187636640/113eb363b6

Conflict resolution can be practiced at school

This is how a role play developed by the conflict resolution organisation CMI begins, this time at Helsingin Suomalainen Yhteiskoulu (SYK) in Helsinki. In the role play, SYK high school students are tasked with solving the conflict described above, peacefully through dialogue.

Supporting dialogue is one of CMI’s most important ways of working to resolve differences of opinion and foster peace in some of the world’s most difficult situations. The aim of dialogue is to build trust between all the sides involved in a conflict. Once mutual trust has started to emerge, all those involved can start to search for solutions what they could all accept and commit to.

Disputes and disagreements are what are fundamentally at issue both in school rows and in international conflicts. Amongst the other conceptual tools contained in the materials package is a role play in which students must use dialogue to solve a conflict that has broken out near the school. The aim of the dialogue is to demonstrate that any kind of conflict can be resolved peacefully if only there is the skill and the will to do so.

The aforementioned conflict resolution exercise is part of a materials package created by CMI for the Ahtisaari Days, which are held every November. The materials can be freely used by teachers to supplement their teaching, as they are compatible with the new school curriculum. This allows junior high and high school students to start solving conflicts in their own school.

Students in their third year of high school at Helsingin Suomalainen Yhteiskoulu got to try their hand at problem-solving under the guidance of CMI’s expert Denis Matveev.

Main characters and bridge-builders

The role play is directed by the teacher. In SYK’s pilot exercise, CMI’s Denis Matveev took the role of teacher.

At the outset of the exercise, Matveev assigns each student a character. Each of the ten students gathered around Matveev is handed a brief description of their role, the background of the character, and how he or she feels.

The far-right activist will be played by Patrick Haponen, and the fanatical Muslim by Ada Segerstam.

After the roles have been given out, the Segerstam sits on the floor in the corner of a small corner room to get the feel for her character.

“My character isn’t very diplomatic, he acts on emotion rather than reason,” Segerstam begins.

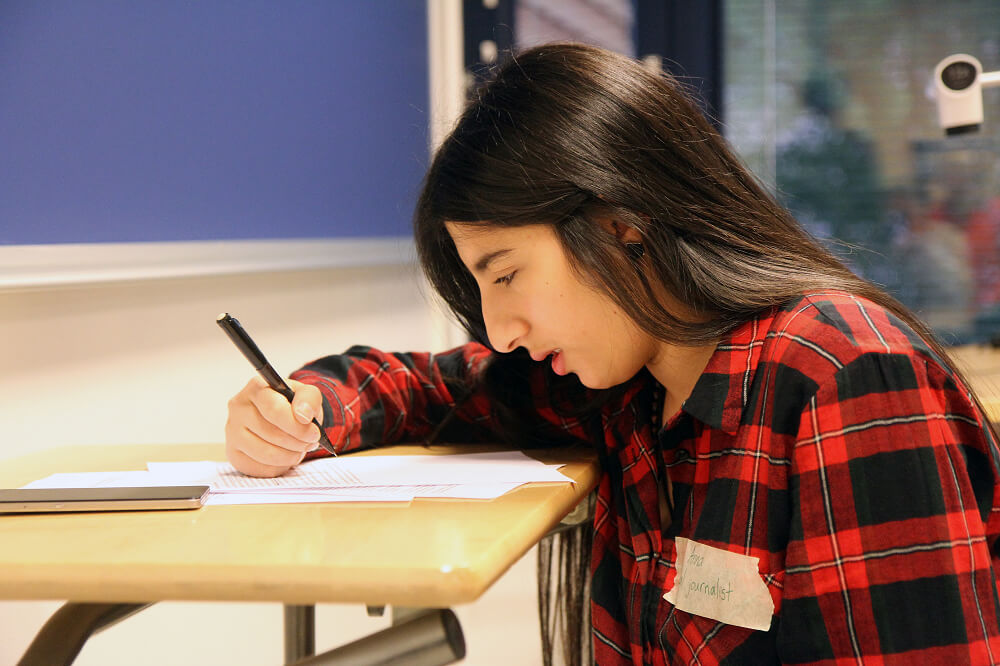

Also needed are characters who will try to act as peacemakers, bridge-builders between Haponen’s and Segerstam’s characters. Nina Zhao, for one, plays a worker with a non-governmental organisation that helps refugees. Anna Kristiina El-Khoury plays a local journalist who is worried about the tension surrounding the recent arrival of refugees in the town.

Matveev encourages the students to keep in mind that the aim of the exercise is not to try to put themselves in the imposing shoes of heads of State or other high-level figures.

“This could happen in Finnish society, in a Helsinki school. So just step into the shoes of your character. You don’t need to know anything about far-off countries,” Matveev reassures them.

Anna Kristiina El-Khoury considers how best to take on role of the journalist.

How could the conflict be resolved?

Those who first arrive on the scene after the violent row has broken out between the two main characters try to put an end to it.

“This is not the best way or place to settle your differences,” urges Nina Zhao’s character, the NGO worker, who has come to pick up her child from school.

The others pull the two main characters apart. The work of conflict resolution begins. The young far-right activist emphasises that he has a right to express his opinion. In his view, the man’s attack on him proves that Muslim refugees cannot integrate into Finnish society.

“They’re all violent. We should limit the amount of refugees.”

The journalist and NGO worker try to get the activist to understand that he should not generalise from the violent action of a single person to all Muslims. The NGO worker says that Finland has a moral obligation to help those who are fleeing war, and that Finns themselves were helped when the country was at war in the past.

The Muslim man points out that he is not a refugee but a Finnish citizen who has been in the country for 18 years. Tarring all Muslims with the one brush and putting down their religion makes his blood boil, he says.

“I can’t allow people to talk rubbish. If he has a right to talk like that, then I have the right to blow myself up,” asserts the man, played by Segerstam.

The man then complains that Westerners are apathetic about the “hell” that people in the Middle East are living.

“I’m tired of it.”

The bridge-builders remind the man that creating divides and violence solve nothing.

Eventually the warring parties agree to sit down together to talk. They come to agree that violence is wrong, and that it is important for immigrants to adapt to Finnish society.

The NGO worker invites the two to come and work in the organisation. Some of the class feel that this is not a very convincing solution to the conflict.

Matveev, however, considers this solution a good example of a reconciliation in which both sides gain. After all, the attitudes of both the main characters have been strongly shaped by unemployment.

“You found a creative solution. Both of them got work, and at the same time an opportunity to work together in cooperation,” Matveev says encouragingly.

The neutrality of the bridge-builders was discussed after the exercise. Some felt that the far-right activist got less support than the Muslim fanatic, and the conflict-resolvers were also cooler toward the former character.

Segerstam says she was told her character would not have to apologise.

“Remember that the task of a bridge-builder is not to tell any side in the conflict how they should be. The task instead is to present open questions, for instance about how that person feels,” Matveev says.

Patrick Haponen, who played the far-right agitator, and the fanatically religious Muslim, played by Ada Segerstam, shake hands once their row is solved.

“It’s part of a well-rounded education to be able to resolve conflicts.”

Stepping into another person’s shoes was not so easy for the students.

“It was really hard to get a grasp of how the character thinks, and to improvise from there,” Segerstam says.

“It was hard at the start. I was nervous. Gradually I got used to the role and things started to work – I got a feel for the kind of things I should say,” comments Nina Zhao, who played the NGO worker.

Many in the class were disappointed that there was not enough time to negotiate a more lasting solution to the dispute. But although the exercise passed quickly, the students found it helpful. It showed them how dialogue works, encouraged them to empathise with others, and highlighted the importance of being aware of one’s own behaviour in the midst of a difficult situation.

“I learned how to talk to others in conflict situations,” Zhao says.

The students say it’s likely that a real-life dispute of this kind could occur in a Helsinki school.

“Although we are not all bridge-builders, being able to resolve conflicts is part of a well-rounded education,” concludes Segerstam.